For a change, I am writing a post with a herbal history focus, exploring medicinal recipes. There was an amazing range of plaster recipes in seventeenth century England - belly plasters, foot plasters, head plasters - and here I focus on wrist plasters and their ingredients. I discuss some wrist plaster preparations that might have been used for ague and eye complaints, their ingredients, effectiveness and cautions about toxicity, and why the plasters fell out of favour.

Researching household medicine in the seventeenth century

Readers may be aware that in the past I delved deep into the history of medicine for my doctoral thesis. As a scholarly researcher, I explored thousands of seventeenth-century English handwritten recipes for healing. Some of these recipes gave fascinating insights into the way illness was perceived in those days and the efforts made to alleviate many ailments and pain. For a fuller account of the research, you can see my book publication Household Medicine in Seventeenth-Century England (Bloomsbury, 2016)

Today's plasters are mostly familiar as long thin adhesive cloth dressings from the chemist to protect skin and are a shadow of the past! Traditionally, 'plaisters' were thought of as healing preparations placed on the skin that provided a key element of treatments for all kinds of problems, not just wounds but also agues, eye complaints, pain and other distempers. These plasters were more substantial solid items often consisting of plant materials with resins, tar or wax made into a sticky paste.

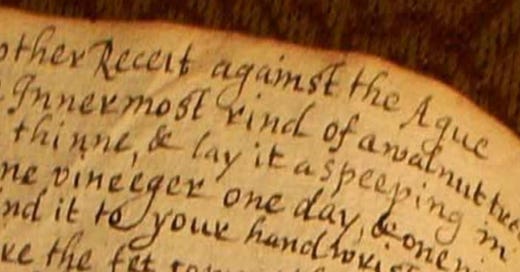

My sources for historical medicinal recipes included both household collections and printed books. There are handwritten recipe collections to be found in most county archives and in institutions such as the Wellcome Library in London. Similarities between printed books from the early modern period and manuscripts in the recipe constituents would not be surprising since there were interchanges between the two. For example, households would likely record the recommendations of both lay visitors and learned medical practitioners, and household receipt collections might be published as a source for others. Here I use adapted examples based on my own recipe transcriptions and sometimes you have to read out loud to realise the words and meanings.

Treating ague in the seventeenth century

Ague in the seventeenth century referred to an 'acute or violent fever', commonly a malarial fever with 'successive fits or paroxysms, consisting of a cold, hot, and sweating stage'. The term might initially have been used for the feverish stage, but was also used for the 'cold, shivering stage'. There were lots of suggestions for cures.

External preparations for ague included ointments, salves, poultices and plasters. One form of preparation which appeared commonly for treating ague, was the wrist plaster. In my search some 35 wrist plasters were found and all but eight recipes were for ague. For example:

For an Ague, Lady Grey

Take the thickest hard soote of a Chimney bay salt pepper of each a like quantity, beat these together till they be small, then put in the yolk of an egg then beat them altogether againe untill it be like a Salet [salve?] when you have soe done Spread it on a cloth and lay it on your wrists, and let it remaine on twenty four hours before you take it of againe.

The recipe above indicated mainly household ingredients, and the application was intended for use overnight. It is not clear whether there would have been any beneficial effects from today's point of view. Other wrist plaster recipes did contain plant ingredients which might have been effective if absorbed through the skin, ingredients such as barberry bark, feverfew and garlic offering hepatic and antibiotic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory, antibiotic actions, respectively:

A medicine to Take The quartaine Ague which I haue proed to doe itt

Take a Shooing horne Screape Soe much of the Inner Side of itt as will taken up heaped upon a Six pence giueing it at a Goeing to bed in a Spoonfull or two of beere the night before the fitt comes and Soe much againe in the Same Manner in the Morning an hower before The fitt Comes and at Goeing to bed that Same night att The Next Morning fasting againe all these fower times Lay on fresh barbary barke and lett it lye fast to both wrists this doe if it preuent not the first fitt The second and the Third in which Time and Gods Blessing it will helpe you.

For an Ague

Take powder of Glass and beat fetherfew bay Salt a little vinegar Mix all These Together and fix Them To The wrists beinge make plaister Misse halfe an hower before The fitt comes and for want of fetherfew a little Rose water.

To cure an ague Lady Westmerland

Take 7 cloves of garlick pilled, one spoonfull of bay salt as many cobwebs as the bignesse of a walnut and beate all these well in a morter and mixe them with Deanes [venice?] treacle, to make it a plaister to spread on browne paper, prickd full of holes, and lay it on the veines of the wrest of both armes an hower before the fit comes, and let it remaine till you expect another fit againe; which time you must renewe it, thus doo 3 times, and sweat upon it euery time you renewe it.

Vehicles for the plaster applications ranged through grease and suet to salt, powdered glass or horn, soot and cobwebs. Some plant ingredients might have been obtained nearby in a field or hedgerow as common weeds such as shepherd's purse, groundsel, celandine and red nettle. Other plant ingredients would have been uncommon and possibly only available in the gardens of wealthy households, such as fig and walnut. Some recipes have 'probatum est' (it is proved) within or added in margins, though this should not be assumed as evidence of actual use.

For An Ague and hath proved very Efectuall

Take A handfull of Sheaperd purse a handfull of Grandsill a handfull of Salladine beate all Together in a Morter and aply Sume of it to both your wrists and fast Six howers after probatum est.

A Medicine To Lay To The wristes and aproved for the Ague

Then Cutt a figg Through The Middeist and Tost it halfe and Soe take up as Much as it Can and Soe hott lay it to both wrists and lett it not be removed in fower or five dayes to ones wriste one figg.

Another To Lay To The wrists

Take one hand of Red Nettles as Much bay salt as Much Cobbwebs boyle all in verjuice till it be soe as to Spread Like a plaister and Soe hott Lay it to The both wrists.

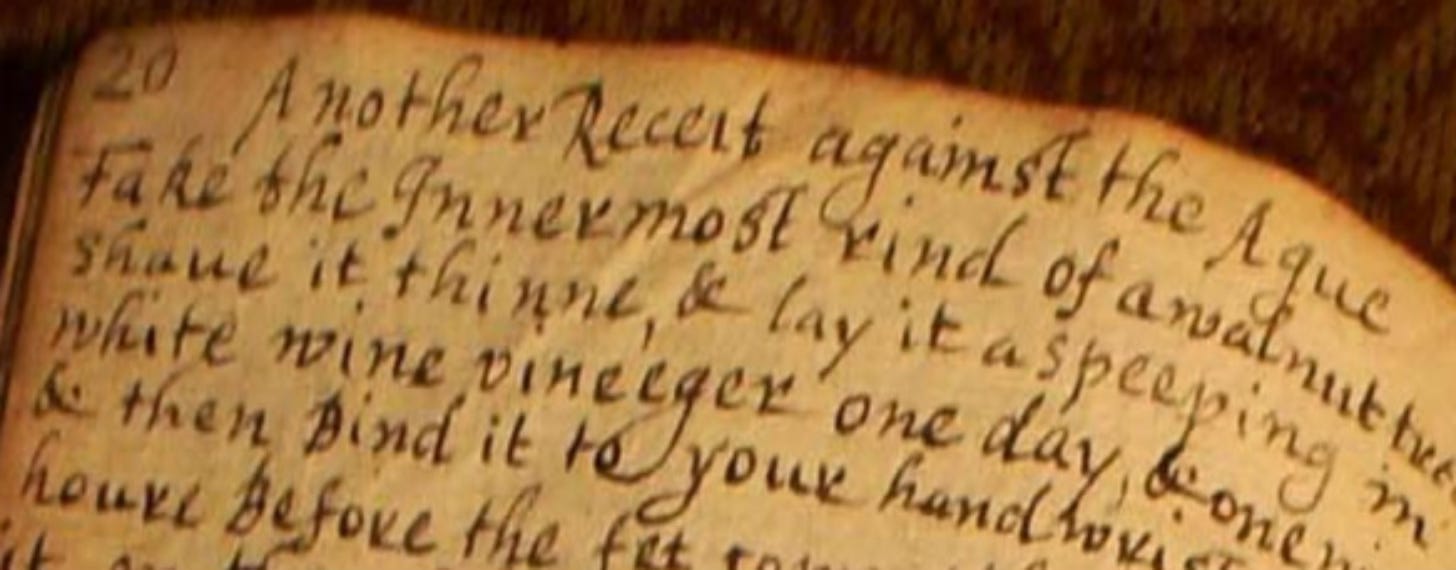

Another Receit against the Ague

Take the Innermost rind of a walnut tree shave it thinne, and lay it a steeping in white wine vinegar one day and one night and then bind it to your hand wrists an houre before the fit commeth and soe keep it on the whole day, from Mr John Whitcomb.

Wrist plasters for the 'pin and web'

Wrist plasters for eye complaints were also found, especially for pin and web. This was likely a term for cataract or corneal opacity, and this could have been caused by various problems such as conjunctivitis or growths. Of 44 recipe preparations located for this condition, the majority were for direct application such as eye drops or eye washes, but seven were listed as wrist plasters. Ingredients in such preparations that were often repeated included celandine, daisies, fennel, ground ivy, hemlock, honey, salt, sugar, wine and woman's milk.

A present remedy for pin and webb

Take daisies, and their rootes, crowsfoote, three cornes of bay salt, and pound them together, and lay unto the contrary hand-wrist twice or thrice applied at the most will cure it.

Several recipes for pin and web included hemlock roots boiled in water bruised with bay salt and bound to the contrary wrist repeatedly. Hemlock was also used in another receipt for an eye complaint:

To lay to the wrist for ye pearle in the eyes

Take the bole armanacke and honey and hemlock of each a quantity alike when it is beaten then mixe it together. then lay it upon new sheeps leather: and lay it to the contrary wrist.

It should be noted that hemlock (Conium maculatum) is a highly toxic plant. Just small amounts of the alkaloid constituents can quickly disrupt muscular control and the nervous system, and fatalities are due to respiratory failure. This is the reason why foraging of plants in the carrot family (Apiaceae or previously Umbelliferae) requires considerable caution as plants like angelica, parsley, wild carrot can be confused with hemlock. Although hemlock has smooth stems and purple blotches, it has similarities to these others in its aromatic ferny leaves and white flower umbels.

Could these remedies have had an effect?

Another wrist plaster recipe was listed for sleeplessness and it incorporated further potentially toxic ingredients. The recipe 'To cause on[e] to Sleepe' included poppy seed, henbane seed, an apple of mandrake beaten with lettuce juice and stood 3 days and nights and 1 dram opium dissolved in wine distilled, mixed with powder of labdanum and myrrh and 'vapour away juice' till thick enough for a plaster to apply to temples or wrists and 'this will make on sleepe in any burninge fever or ffrensie'.

It seems likely that the systemic effects of these active ingredients could have been significant in some traditional recipes. I should add 'Don't try these at home', even if you want to recreate these preparations merely for historical interest! The therapeutic and toxic effects may be much too close for comfort and safety!

I did investigate the possible absorption of plant constituents through the skin. It turns out that use of these plasters at the wrist could have led to absorption of active constituents with some effects. However, the level of absorption would have been low, perhaps less than 10%, thus somewhat ameliorating the dangers of toxic constituents. To further determine the likelihood of absorption we need to consider the dynamics of transdermal absorption for herbs.

Factors affecting absorption are varied, and include the vehicle used, nature and concentration of ingredients, the means of application especially length of time (not linear), covering and the size of area where the preparation is applied. Temperature and humidity can also have an impact. Finally, the location of application is important as it determines the thickness of skin, hairiness and the local blood flow and metabolic activity. Poet and McDougal (2002) reviewed skin absorption of malathion (a highly toxic organophosphate insecticide) and identified the percentage of malathion absorption in different parts of the body. Blood flow is highest in the scalp and scrotum areas though still potentially significant elsewhere except for thickened and hardened areas of skin such as the palms. In general, fatty substances are better absorbed through skin, and the absorption of volatile substances increases if the application is covered over.

Less toxic constituents could have been effective too such as anti-inflammatory sesquiterpenes found in the daisy and feverfew (Jürgens et al., 2022).

The future of plasters as remedies

Plasters have a longstanding use in other traditional medicine systems, and there is continuing use of flexible adhesive patches largely for the treatment of pain in trauma, arthritis and neuralgia. However, the use of external preparations in the UK did start to decrease in the eighteenth century as medicine-making became more commercialised. The wrist plasters seemed to fall out of use during this period. There was increasing interest in internal remedies, especially universal cures. But the possibility of herbal applications using transdermal routes for systemic effect may yet be worth further exploration. Commercial sources have developed topical plasters which can deliver both lipophilic and hydrophilic ingredients, rather than traditional rubber and rosin formulations. Use of nano-particles (Park et al., 2024) and micro-needle arrays is being pursued in clinical research. There may be a come back for some plasters yet!

References

Jürgens FM, Herrmann FC, Robledo SM, et al. 2022. Dermal absorption of sesquiterpene lactones from Arnica tincture. Pharmaceutics 14: 742.

Park JS, Choi JH, Joung MY, et al. 2024. Design of high-payload ascorbyl palmitate nanosuspensions for enhanced skin delivery. Pharmaceutics 16: 171.

Poet TS and McDougal JN. 2002. Minireview: Skin absorption and human risk assessment. Chemico-Biological Interactions 140: 19-34.

Stobart A. 2016. Household medicine in seventeenth-century England. London: Bloomsbury Academic.